By Terry Witt – Spotlight Senior Reporter

Levy County Commissioners have been quietly giving pay raises to their highest-paid administrators each time the road department labor union got a wage increase for decades, but the practice was hidden from public view. It was never a written policy.

Levy County Commissioners this week voted 4-0 to amend their pay procedure policy to include a single paragraph giving department heads and other management employees who work for them the right to get the same pay increases as the road department union employees.

The new policy merely authorizes a practice that has been invisible to the general public and unnoticed by those who pay the bills – the county’s taxpayers for more than two decades.

Former County Attorney Anne Bast Brown spilled the beans in December of 2020 at a county commission meeting when she requested a 3 percent pay raise. When a commissioner asked whether she had received previous raises, she quietly said “only LIUNA raises.” Laborers International Union of North America (LIUNA) Local 639 represents the road department. The board gave Brown the 3 percent raise, which was on top of her previous LIUNA-related raises. Her statement opened a can of worms.

It was the first public admission that she received the same raises as road department laborers through their LIUNA union contact. The union represents the road department as well as low-paid county employees across county government in the LIUNA bargaining unit. The union doesn’t represent county administrators or the management office employees who work for them.

What LIUNA raises meant for Brown, who earned a salary of about $128,000 at the time she retired this year, and County Coordinator Wilbur Dean, who earns about $90,000 annually, as well as other department heads, is that anytime LIUNA negotiated a pay raise for its grass cutters, grader operators and dump truck drivers, administrators like Dean and Brown got the same raises as the union, boosting their salaries even higher.

When the union negotiated a percentage pay raise based on the employee’s salary, the higher paid administrators received a much larger dollar amount than their union counterparts. A 3 percent raise meant the administrators got a raise equal to 3 percent of their salary.

On Oct. 1 this year, the latest LIUNA raises take effect. This is a flat raise of $1,000. It amounts to about 50 cents per hour over the course of a year. Once again, the county’s administrators and other management personnel will receive the same raises as LIUNA.

Giving LIUNA raises to high-paid administrators is legal, according to Ronnie Burris, business agent for LIUNA 630, even though the county is attaching administrative raises to the coattails of lower-paid county road department workers. He said other counties do the same thing, but the difference in Levy County is that practice was a well-kept secret in county government. Tens of thousands of tax dollars over the years were given out in LIUNA raises behind the scenes to high-paid administrators. County officials knew about them. The public didn’t.

Are the raises ethical?

“That’s part of the problem. They’re going to get a lot bigger raise than my people are,” Burris said. “If it’s done on a percentage basis, they make a much higher rate. If you’re making $100,000 a year and you get 3 percent, the supervisors are getting a lot more than my people. A flat rate doesn’t make them any further apart in salary, but a percentage raise is big.”

The county commission gave out percentage raises many times in the past.

Spotlight began digging into the unwritten pay raise policy through public records requests after Brown’s public admission in December of 2020 that she was receiving LIUNA raises. The county is advertising to find her replacement. The first round of ads was a failure. Two attorneys applied for the job. The commission’s choice to be the next county attorney, state prosecutor Glenn Bryan, declined the county’s offer.

Jacqueline Martin, county human resources director, brought the written pay raise policy to the board on Tuesday, Aug. 3, noting the practice of giving the union raises to non-union employees has been around for years. Dean, who served as a county commissioner from 1992-2000 told Spotlight earlier that he thinks the practice dates back to his county commissioner days.

“This just spells out what we have done in the past,” Martin said. “Throughout the years we have done this. At any point, the board can decide that they don’t want to follow the procedure and change the way we do things.”

Spotlight Founder Linda Cooper criticized the practice of giving high-paid administrators the same percentage raises as lower-paid union workers or giving the same flat rate raises as lower-paid union workers. She noted the county doesn’t evaluate department heads to find out if they merited an increase in pay through the union contract.

“These same highly paid employees are not given performance evaluations. Most have take-home vehicles and are salaried, some are barely putting in 20 hours a week,” she said.

The practice of giving the LIUNA raises results in a serious gap in accountability, she said.

“For example, your county coordinator received a $1.54 per hour pay raise on June 20, 2020, based on the union contract. The HR director signed off as his department head. The HR director reports to the county coordinator. How is she authorized to sign his Personal Action Form to approve the raise?” she said. “Three months later on Sept. 26, 2020, the county coordinator received an additional 25 cents per hour and he authorized his own raise. Shouldn’t the board or at least the chairman approve the raise? You can’t continue to tax and spend your way out of this.”

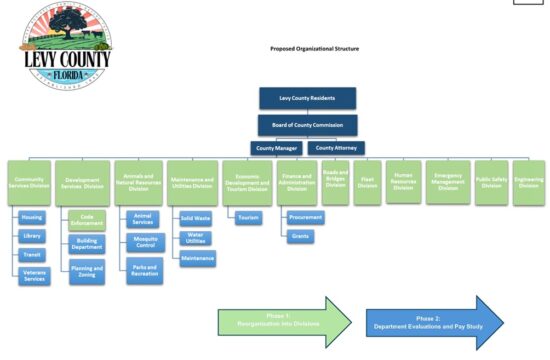

“You are about at the point where you have to do some type of restructuring with the number of department heads, as well as doing something about these automatic pay raises based on union contracts that are not part of the bargaining unit. You can’t keep providing take-home vehicles for people not on call, and you need more up-to-date retirement options. You can’t keep putting your head in the sand. Maybe it’s time to consider a 20 year-and-out option or other retirement plans. Some employees have 25 or more years on the job. Most employees burn out after 20,” she added.”

Cooper also said certain department heads aren’t even showing up for work at times. Dean said he is unaware of any department heads not going to work.

“As far as each department head not being here, I’m not aware of that,” Dean said.

“Well, there are security cameras if you want to check them,” Cooper responded.

“Do they have to be sitting at a certain spot?” Dean asked.

“No, just coming through the gate,” Cooper responded.

Commission Chairman John Meeks disagreed with Cooper’s remarks.

“Here’s my comments, although they will be twisted and taken out of context. If you’re insinuating that people who are in leadership positions that bear all the responsibility for how a department is run, or if they are in a position of responsibility overlooking other employees, shouldn’t be granted the same raise as an employee, I have a problem with that because they are the very brunt of responsibility,” Meeks said.

“Number two, you’re 20 years and out plan; that sounds great on paper but you want people to give 20 years of their life and in most cases the best 20 years of their life? Let’s say they came to work for the county when they’re 25 and they work until they’re 45 and then we’re supposed to turn them out in the street at 45 years old with fewer options to be employed and higher insurance costs?”

“The security of having your job every day, the security of knowing your paycheck is going to be in the bank every week, the security of knowing that you have provided security for yourself, and your family, and the fact that you are building toward a pension plan; they are sacrificing money on the outside in the private sector for security in the public sector,” Meeks said.

“There you go twisting my words,” Cooper responded. “I said options. You don’t need to have someone here 40 years; whatever it is, 20, 30, 40 years. Because you’re burnt out, you’re not an effective employee. I said options, not mandatory. You need to do something for 30 to 40-year employees, giving them an out.”

Meeks responded that the county can’t afford to pay for employee insurance. He said the county can’t afford to buy people out by giving them 30 weeks of salary for 30 years on the job.

“Speaking of the head in the sand. You can’t expect government employees to have better jobs than the private sector. Government employees are paid during hurricanes,” Cooper said. “They get great holiday pay. They get great health insurance on the backs of taxpayers,” she responded.

———————

Board of County Commission Regular Meeting August 3, 2021; Posted August 8, 2021