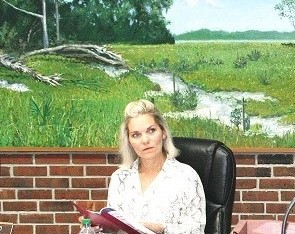

Dr. Maggie Labarta discusses the rising number of Baker Acts in Levy County.

By Terry Witt – Spotlight Senior Reporter – (Part II of Series Discussing Baker Acts)

The forced removal of public school students from classrooms on grounds they may be mentally ill or a threat to the classmates and staff has become more frequent in Levy County schools. The number of Baker Acted Levy County students in 2018-19 increased by 16 from the previous year, according to sheriff’s records.

The Florida Mental Health Act of 1971, or Baker Act as it is commonly called, authorizes a doctor, certified mental health professional, judge or law enforcement officer to order the removal of a child from a school under the Baker Act. Students are transported in handcuffs in the back of a sheriff’s patrol car to a crisis stabilization unit in Gainesville for evaluation by a clinician within 12 hours of being removed from school, according to Dr. Maggie Labarta, chief executive officer of Meridian Behavioral Healthcare, the organization that receives Baker Acted Levy County students at its Gainesville Crisis Stabilization Unit.

Typically the assessments at CSU are done by a master’s level social worker/counselor when the student arrives for an evaluation. The evaluation is overseen by a licensed supervisor or doctor. The licensed clinician or doctor decides on whether to admit the student for further evaluation at CSU or refer them to outpatient services, according to Meridian.

Deputies, Rising Baker Acts

In Levy County schools, more often than not, the job of determining whether a student should be Baker Acted and removed from school, falls on a school resource officer with minimal training in mental health issues. Deputies determine whether a student is a threat to themselves or others. Deputies shoulder the responsibility of Baker Acting students largely because county schools aren’t staffed most of the time by licensed mental health professionals who could make the call.

Labarta believes there are two major causes for the rise in student Baker Acts. She said more is known today about child mental illness than in the past, and she said the massacre of 17 students and faculty on Valentine’s Day at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla. is also a factor in the rise of Baker Acts.

Labarta, who holds a Ph.D. in clinical psychology, said there was a time in the mental health field when doctors didn’t think a child could be depressed. They know differently today. Children can be depressed. They can suffer from other mental health illnesses.

Child Mental Health

“There has been a huge growing awareness of mental health issues facing children and I think that has to do with pressure from peers, bullying, and their amazing and continuous presence on social media,” Labarta said. “We were all called names in school; we all had a kid that hated us and picked fights, but it didn’t follow us home; it didn’t necessarily follow us when we went out to play baseball down the street with our friends. We spent a lot of time on bikes with kids we liked and they liked us and we didn’t focus on that kid that picked on us consistently,” she said.

“That doesn’t go away now. They go home to it. I think social media has been clearly shown to increase the stress on these kids. The economic downturn that stressed out families; the families were under more pressure and perhaps less attentive to what’s going on with the kids. So there’s been more pressure on children that has made childhood harder to be honest. At the same time, we’re becoming more aware that these mental health problems exist in children.”

One of the alternatives for dealing with child mental illness has been the Baker Act, she said.

Labarta said kids that act out and misbehave are less likely to be arrested today than to be Baker Acted. She said the rate of school arrests is decreasing at the same rate Baker Acts are increasing. Sheriff’s records appear to bear this out. In the year 2017-18 there were 7 arrests and 25 Baker Acts of Levy County students. In the year 2018-19, there were 2 arrests and 41 Baker Acts, according to sheriff’s records.

More than Just CYA

The Valentine’s Day murders in Parkland have placed school officials under a microscope. They are keenly aware that if they fail to identify a student that might have the capacity for violence the blame would be placed squarely on them.

“Who wants to be the person who misses it and didn’t act to save the other kids; who wants to think this child in front me could go off and do something like this, and if I had Baker Acted them they wouldn’t; who wants to be that person, right, who saw the child and did nothing. And now you have more school resource officers, because many of the schools added SROs, so there’s an easy vehicle for the Baker Act,” Labarta said.

Labarta said Meridian’s evaluations of Baker Acted students doubled after the Valentine’s Day massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in February of 2018.

“Our CSU census doubled immediately after for children, because now you add another wrinkle to that. Do you want to be part of Marjory Stoneman Douglas and the cops that responded to that and be told you failed to identify – Right? So nobody wants to believe or see, and I don’t think it’s just CYA. I think it’s nobody wants to think I could have intervened and didn’t,” she said.

Impacts from Trauma

Labarta said the new approach to evaluating a child is known as “trauma informed care.” They don’t ask the child what is wrong when they are misbehaving, or what is the matter with you? Doctors are finding many kids have a significant trauma history. The data collected by Meridian indicates 9 to 15 percent of the children it evaluates have a primary trauma diagnosis.

“They are post-traumatic stress, abuse and neglect, being in a serious car accident; something traumatic has happened or repeated trauma has happened,” she said. “So we have come to understand kids who have trauma; that their brain is essentially short-circuited. You go from fight-flight being a one-time response, a one-time thing, to a continuous state of existence.”

When a child is continuously exposed to domestic violence in their home, they live in trauma. It never stops, Larbarta said.

“If Mom is constantly hiding and I am the only thing between them and my little brother, I am constantly braced for a fight, am constantly braced for violence,” she said. “You look at me the wrong way and I’m not going to give you a second chance.”

Labarta said Meridian tries to communicate back to the schools with information about what the clinician has learned from evaluating the child, but talking to the school requires parental consent because families have a right to privacy.

“Most parents don’t like the fact that their kid’s been Baker Acted. It’s not a pleasant thing to be called from school and say your kid’s in the back of a police car on the way to Meridian or Shands. The best way we work with you and your child to keep this from happening is to have a really solid relationship with the school where we can help them understand what might help, and what the triggers are for this child’s behavior that caused this Baker Act,” Labarta said.

Shands operates an 81-bed psychiatric hospital in Gainesville. Some of the more severe mental illness cases go to the Shands hospital. But sheriff’s office officials can’t recall ever taking a Levy County student from school to the psychiatric hospital. The sheriff’s office says they deliver all their students to Meridian’s CSU in Gainesville.

——–

8-28-19 Part II-A: Series on Levy County Student Baker Acts – Interview with Dr. Maggie Labarta, chief executive officer of Meridian Behavioral Healthcare.

Posted August 29, 2019